Right-engineering, right-documenting

You will often be told that software engineers have a tendency to under-document, and to over-engineer; but truth be told, you also find cases where engineers have over-documented, or under-engineered, and it’s equally damaging. While a lot about it is very subjective, and there is no single right level of documentation or engineering, there are key landmarks to keep in mind.

- Right-documenting

On my first week at Apple, I was appalled when I heard: “We don’t document our applications here, it is simply part of the Apple culture”. At first, I thought I was simply talking with a particularly lazy team who made up some excuse, but it was echoed a few weeks later with a post on Apple Web (the main internal portal) by Apple University (the team in charge of studying and evangelizing internally about Apple’s culture). It couldn’t get much more official than that. I was very intrigued, so I asked around, and I came to understand that it was a lot like most company culture items in every company: it was not entirely true, but more designed to prevent people from doing too much of the opposite. Since they had noticed that over-documentation could often be in the way of flexible innovation, and that they worry so much about innovation, they were willing to have more of the downsides of under-documenting (people doing duplicate work without knowing, application running and no one knows how they work), rather then the opposite.

- Items of documentation

You will often hear it said that a developer doesn’t write code for a computer, but primarily for another developer to read it. Assume that a developer who knows nothing about the decisions you made on your project, and what you were trying to do, will take it over and need to understand it. What can you do today to help them get up to speed efficiently? Here’s the killer motivation: more often than not, that developer is actually you, months from now, after working on many other projects and forgetting all about the decisions you had made. Just like every developer, you will reach that moment where you hate your past self for not having documented better. You can consider anything that helps that future developer understand your decisions and get into your code is an item of documentation, such as:

The most obvious: architectural documentation , documenting the most high-level choices you made. It shouldn’t necessarily contain any code, but should simply explain in the most concise and digestible way possible some of the choices that will allow to understand how the code is organized.

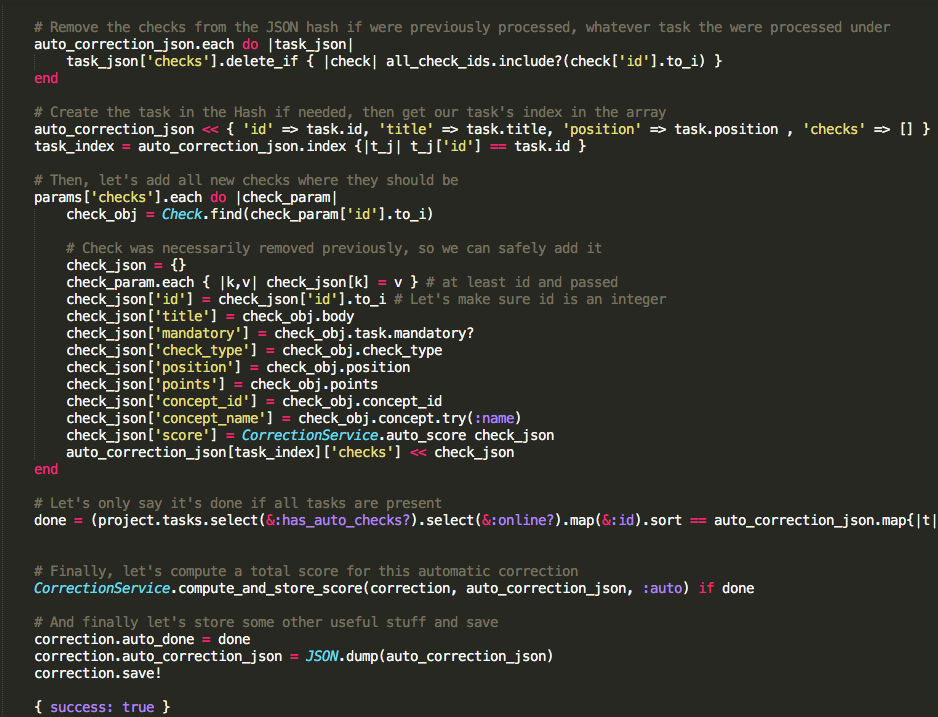

comments are best way to document what the code is doing at the narrow level:

Comments to describe your functions (even more so if your code is meant to be reused by other people): you may want to look into the syntaxes that are conventional in the language you’re using. There might be documentation generators using the comments if they’re input properly.

Comments inside functions: they should be short and descriptive enough that when a developer browses through the code reading only those comments, they understand what each step is, and the whole sequence of what happens.

This piece of code is part of the automated review system; it receives the results and saves them in the intranet’s database, after some processing. Since the code here manipulates data in a way that is hard to read back later, I had been especially explicit in the comments about what each bit is doing, without needing to read anything of the code. (I swear I didn’t edit anything for the sake of this screenshot!)

Names of functions and variables should represent what they’re about without ambiguity. If it would be too long to explain for the size of a variable name, add a comment before the line where you created it, to explain what it is (the next developer, not understanding what it is, will naturally try to find where it was created to try to figure out where it comes from).

Indentation of the code must be properly achieved, so that if the comment and name functions are not explicit enough for what the developer needs to know, they can dive into the code in the most readable way possible.

The Git commit messages, so that a developer who is trying to figure out the chronology of events will at a glance.

Always put a

README.mdfile in your project. It’s even more relevant as you’ll push your projects on GitHub, since that’s what GitHub displays on your project’s homepage. AREADME.mdfile is like the about page of your project, introducing newcomers to what it’s about, how to set it up, its licence information, the process people must follow to contribute to it, … To be clear: you don’t have to have a full README file for every little project you work on, but you should definitely have one for longer projects.

- Symptoms and risks of over-documenting

Take some time to try and pretend wiping your brain and knowledge about the project, and having to learn everything from scratch about how it’s made. Write your documentation for the person you are when you do that.

Even create code when uncommented, looks like code spaghetti when you look at it first, and it's very hard and time-consuming to take one's first steps into it

If you make your code open-source, no one will take the time to understand your code if it’s not well-documented, and what could have been a great open-source project will stall before even existing.

That one day of the year when you’re home with the flu, and your brain doesn’t work right, you’re going to be very happy that when your coworker contacts you with a blocking issue and asks you how the heck this gets fixed, you’re able to just reply “RTFM”, turn Netflix off, and doze off a bit.

Also, in a larger company where it’s likely that several teams might need to build similar things, not documenting or communicating about what you’re building could mean that someone will redo it entirely from scratch while they could simply have used what you built. The opposite may happen: you suddenly realize that the thing you’ve been working on had already been done by someone else who never told anyone.

- Right-engineering

Gauging a level of engineering has a lot to do with planning for the future, avoiding to over-complicate things, and also sometimes with levels of abstraction.

Let’s take a step back with a nice physical-world allegory.

Let’s say that you are trying to accomplish a task, which is: sending 10 tennis balls into a basket. Here are two extreme possibilities to handle the issue:

either you’re doing it in the most naive way, grab a tennis ball, throw it in the basket, start over 9 times with the other balls.

or, you’re building a small catapult, smart enough that when you push a button, it will grab the first ball by itself, throw it exactly right, grab the second one, etc, with no need for you to intervene. The next day, you’re being told that you have to throw 10 golf balls. If you took the first path, that’s simple enough: grab the first golf ball, throw it, repeat. But if you used the catapult, you’re at a loss: your catapult was built for balls that weigh the same as a tennis ball, not a golf ball. You must reconstruct a new catapult from scratch. By abstracting how an object is thrown as much as you could, without consideration with things that were likely to need to be done in the future, you’ve over-engineered your system with your smart catapult, and now it’s unusable.

The next day, you’re being told that you now have to throw 100 tennis balls, and 100 golf balls. If you’ve been a catapult builder, you’re happy: give all of those to both your catapults, and they’ll manage everything for you. If you’ve been a thrower, you must be freaking out: because you haven’t tried to abstract how an object gets thrown, and therefore have under engineered your system, you now have to do everything in a way that is impractical.

Once you are very familiar with a technology, you will tend to over engineer things more, because one feels smart doing that, and throwing 10 tennis balls sounds annoying. Advanced developers tend to come up with systems that are so elegant for their use case, that it will be very hard to change it for the future use cases. To make the right decision about level of engineering, there is a tradeoff to find about keeping things simple so that they keep flexible, and making things engineered enough that are well-maintainable.

Here are a few nice links about over engineering: